Excellent update, Mr. President. Hurrah for Britain!! Round the flag effect and Healey's excellent handling of the war drowned out any chances of the Tory regaining both the parliamentary majority and 10 Downing Street for the rest of the 80. Having said that, I'm wondering if Foot and Benn's resignation from the cabinet would have effects on Labour internal politics. From what I remember, OTL Labour at this period was very bitterly divided, with the militant faction like Degsy Hatton causing problems.Chapter 157 - Don’t You Want Me?: The Falklands Crisis of 1982Above: Leopoldo Galtieri, President de facto of Argentina (left); map of the Falkland Islands (center); Denis Healey, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (right).

“Don't. Don't you want me?

You know I can't believe it when I hear that you won't see me

Don't. Don't you want me?

You know I don't believe you when you say that you don't need me

It's much too late to find

When you think you've changed your mind

You'd better change it back or we will both be sorry

Don't you want me, baby?

Don't you want me? Oh!

Don't you want me, baby?

Don't you want me? Oh!” - “Don’t You Want Me?” by the Human League

“The Falklands thing was a fight between two bald men over a comb.” - Jorge Luis Borges

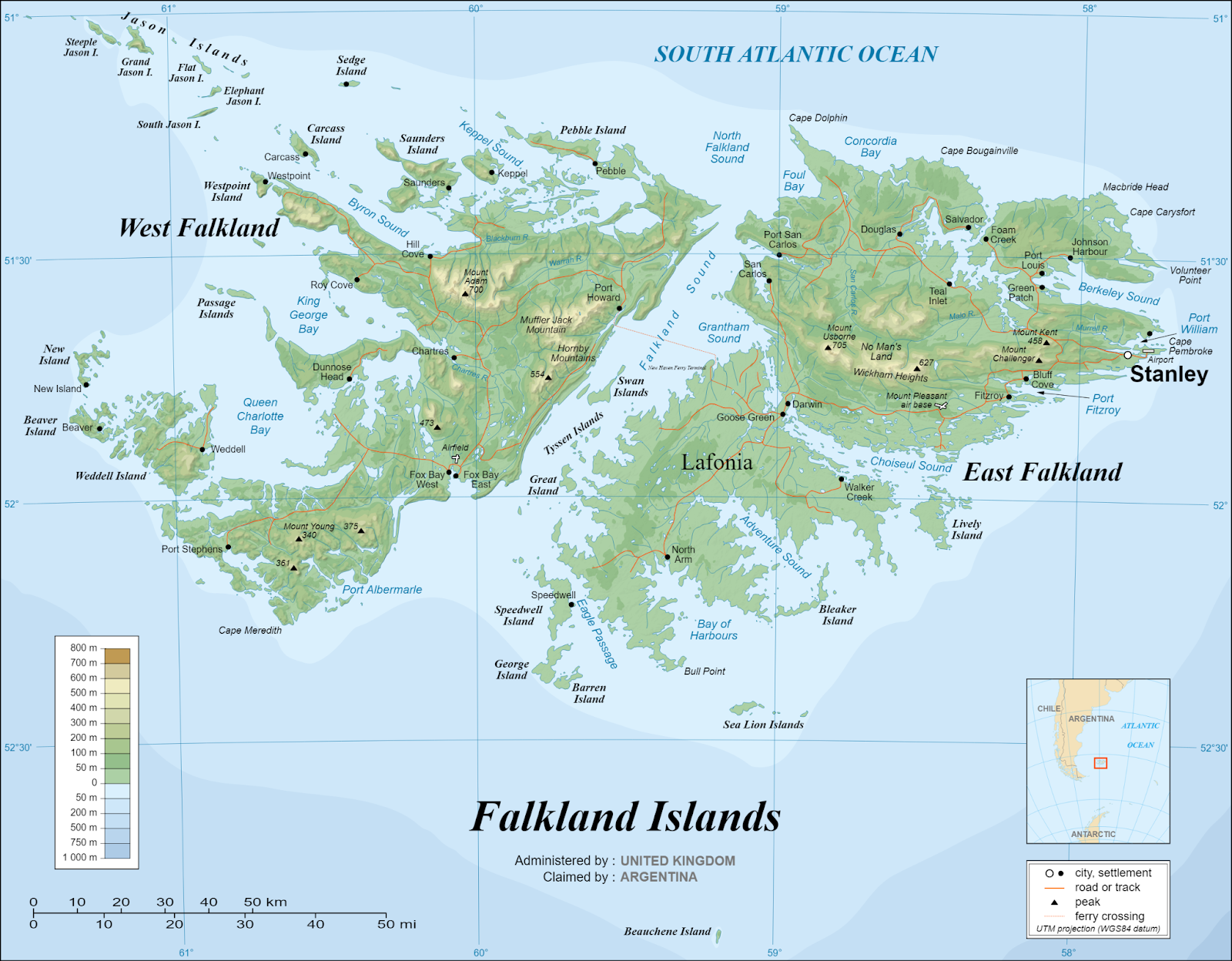

In 1965, the United Nations called upon Argentina and the United Kingdom to reach a settlement of the sovereignty dispute over the Falkland Islands - an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf.

The principal islands are about 480 kilometers east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about 1,210 km from Cape Dubouzet at the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, at a latitude of about 52°S. The archipelago, with an area of 12,000 square kilometers, comprises East Falkland, West Falkland, and 776 smaller islands. As a British overseas territory, the Falklands have internal self-governance, but the United Kingdom takes responsibility for their defense and foreign affairs. The capital and largest settlement is Stanley on East Falkland.

In the mid 1960s, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) regarded the islands as a nuisance and barrier to UK trade with South America. Therefore, while confident of British sovereignty, the FCO was initially prepared to cede the islands to Argentina. When news of a proposed transfer broke in 1968 however, the British citizens living on the islands reacted with disbelief and fury. They, on the whole, did not want to be transferred.

Back in Westminster, elements sympathetic with the plight of the islanders were able to organize an effective parliamentary lobby to frustrate the FCO’s plans. Negotiations continued, but in general failed to make meaningful progress; the islanders steadfastly refused to consider Argentine sovereignty on one side, whilst Argentina would not compromise over sovereignty on the other. The FCO then sought to make the islands dependent on Argentina, hoping this would make the islanders more amenable to Argentine sovereignty. Despite these efforts, however, Islander resistance persisted.

In 1977, then-British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, in response to heightened tensions in the region and the Argentine occupation of Southern Thule, secretly sent a force of two frigates and a nuclear-powered submarine, HMS Dreadnought, to the South Atlantic, codenamed Operation Apprentice. It is unclear whether the Argentine government was aware of their presence, but British sources state that they were advised of it through informal channels. Nevertheless, talks with Buenos Aires on Falklands sovereignty and economic cooperation opened in December of that year proved inconclusive.

The following year, with the Labour Party under Denis Healey swept back into power, the new PM made the decision to stop pressuring the islanders. “If they want to remain British,” Healey told his cabinet. “Then by all means, let them be British”.

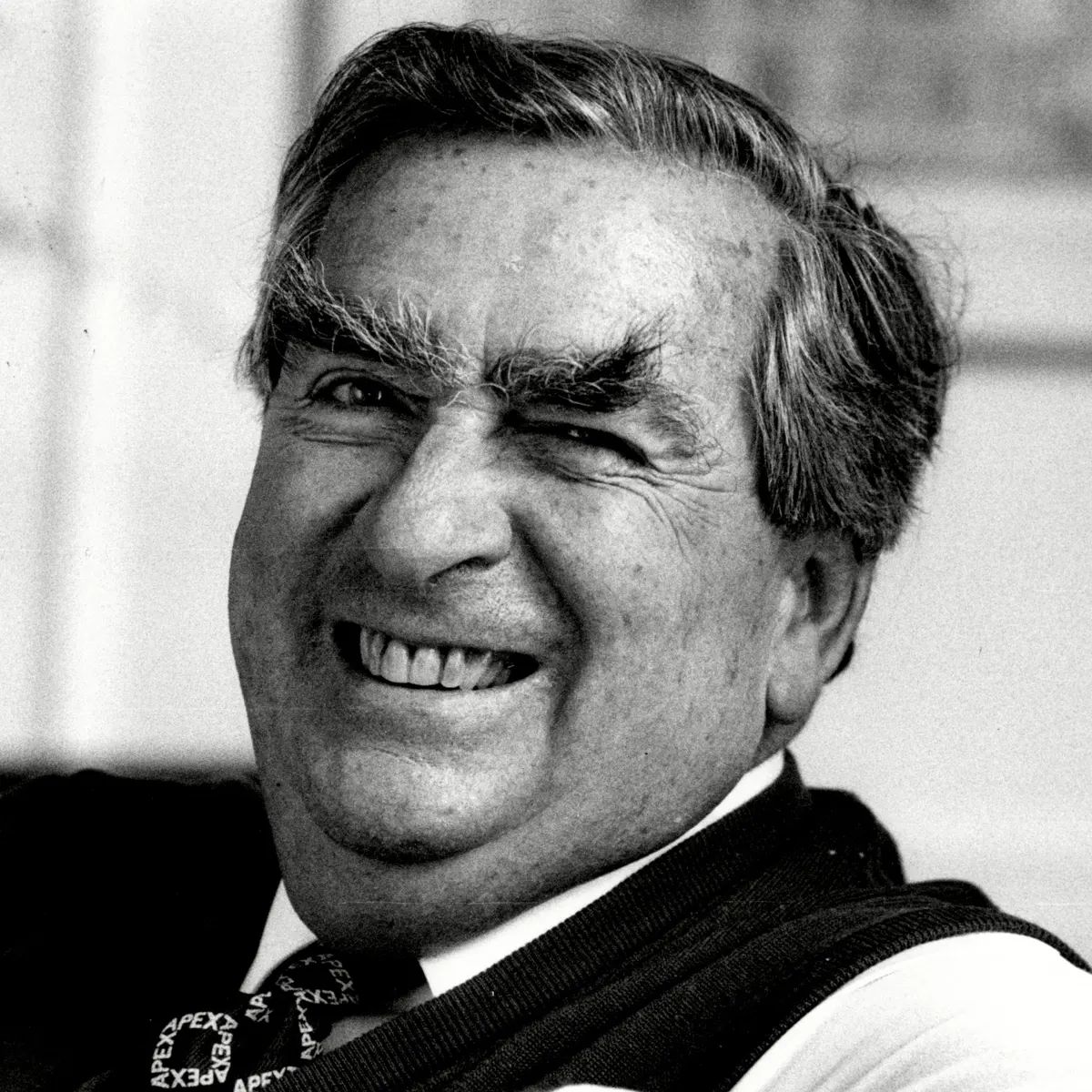

Meanwhile, the other nation involved in the dispute - Argentina - had been in the midst of devastating economic stagnation and large-scale civil unrest against the National Reorganization Process, the military junta that had governed the country since 1976. Backed by the Bush Administration as part of Operation Condor, the Argentine junta held an abominable human rights record and was deeply unpopular with the populace of the country. A further shake up occurred at the tail end of 1981, when a new junta came to power, headed by General Leopoldo Galtieri as Acting President, supported by Air Brigadier Basilio Lami Dozo and Admiral Jorge Anaya. Of these men, Admiral Anaya was the most hawkish on the Falklands Issue. Indeed, he was supremely confident that, should the Argentines employ military force to seize the islands, “then the British will not intervene”.

Above: Second “March of Resistance” held on December 9th - 10th, 1982. The flag reads "Let the 30,000 who disappeared show up alive” (desaparecidos in Spanish); this event was organized by the “Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo”, a human rights organization dedicated to protesting the military junta.

Admiral Amaya began to bend Acting President Galtieri’s ear toward military intervention in the Falklands. Through a (largely performative and ceremonial) invasion, Argentina could seize new territory, and punch a “fading” Great Power in the nose without having to worry about any potential repercussions. This could, Amaya argued, distract public attention in Argentina away from the country’s chronic economic depression and the ongoing human rights violations of the “Dirty War”. If successful, defeating and humiliating Britain could only bolster Argentine prestige and raise the junta’s legitimacy. Galtieri began to formulate a plan.

On March 19th, 1982, a group of Argentine scrap metal merchants (which had been infiltrated by Argentine Marines) raised the Argentine flag at South Georgia Island, a provocative act that would later be seen as the first offensive action in the forthcoming “Falklands War.”

In response, the Royal Navy ice patrol vessel HMS Endurance was dispatched from Stanley to South Georgia on the 25th. The Argentine military junta, suspecting that the UK would reinforce its South Atlantic Forces, ordered the invasion of the Falkland Islands to be brought forward to April 2nd.

Despite numerous warnings by Royal Navy captain Nicholas Barker - commanding officer of the Endurance - and others in the South Atlantic, the British government was initially shocked by Argentine attacks on the islands. Such bold action on the part of the Argentines had not been predicted, especially with new rounds of talks scheduled to take place at the UN later in the year. For his part, Barker believed that Defence Secretary John Silkin had “practically invited” the Argentines to invade. The year prior, Silkin had made comments in his 1981 review of British Defence policy that as a “cost saving measure”, the Royal Navy should withdraw Endurance - the last of its ships in the South Atlantic - from the region indefinitely. Barker believed that Buenos Aires took these comments as confirmation that the British would “not lift a finger” to protect the islands.

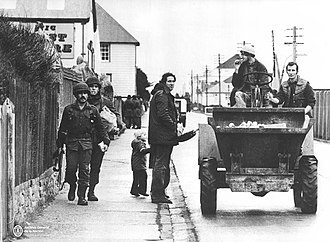

On April 2nd, 1982, Argentine forces launched Operation Rosario - a series of amphibious landings across the Falkland Islands. The invasion was met with a fierce but brief defense organized by the Falkland Islands' Governor Sir Rex Hunt, giving command to Major Mike Norman of the Royal Marines. The local garrison consisted of 68 marines and 11 naval hydrographers, assisted by 23 volunteers of the Falkland Islands Defence Force (FIDF), who had few weapons and were mostly used as lookouts. The Argentine forces began their attack by seizing an empty barracks at Moody Brook, then moving on Government House - the official residence of the Governor - in Stanley. When it became clear to Governor Hunt that further resistance was futile, and only likely to get his small detachment killed, he ordered a ceasefire and surrendered. The governor, his family and the British military personnel were flown to Argentina that afternoon and later repatriated to the United Kingdom.

Above: Argentine soldiers interact with Falkland Islanders during the opening stages of the invasion (left); Sir Rex Hunt, colonial Governor of the Falklands, who mounted a brave defense, then surrendered when it became clear that he could not hope to hold out without reinforcements from the Home Islands (right).

Prior to the April 2nd invasion, the British had already taken action of their own.

Responding to the attack on South Georgia on March 29th, the Royal Navy dispatched the nuclear submarines HMS Spartan from Gibraltar, and HMS Splendid from Scotland, both to support Endurance. Supply ships, such as the Fort Austin were also dispatched from the Mediterranean. Dispatching additional ships was considered, but initially rejected, as the Defence Ministry did not wish to endanger other operational commitments until they knew for certain the seriousness of the threat posed by the Argentine invasion.

On the 30th of March, an emergency cabinet meeting was called back at 10 Downing Street in London. Prime Minister Denis Healey chaired the meeting. He was said to be taking the entire situation “deathly seriously”, referring to it, even at this fairly early stage, as a “crisis in the making”. At this meeting, the First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, Admiral Sir Henry Leach, advised that “Britain could and should send a fully outfitted task force if the islands are invaded”. The cabinet, led by Healey, agreed.

Well, mostly agreed.

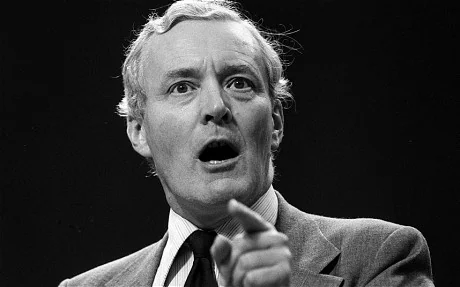

Two ministers - Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council Michael Foot; and Secretary of State for Energy Tony Benn - both opposed the move as a matter of principle. Both men were staunch anti-war pacifists. They had built their reputation in the Labour Party during the 1960s and 70s as opponents of first American and Australian involvement in Southeast Asia and later, British involvement in Rhodesia. Though they sympathized with the plight of the Islanders, neither man supported going to war with Argentina over the islands. Instead, Benn and Foot voiced their preference that the matter be submitted to the International Court at the Hague for arbitration.

Above: Tony Benn (left) and Michael Foot (right); the two members of Healey’s Ministry who disagreed with the Prime Minister’s authorization of the use of force against Argentina during the Falklands Crisis.

The PM balked. Famously, Healey responded to the ministers’ complaints by declaring, “Arbitration? Gentlemen, they’re already shooting down there!” The time for arbitration has passed.”

Healey’s outlook on the crisis was determined by a number of factors. Chief among them was his view of geopolitics. Though certainly pragmatic and flexible, Healey was also an old school Cold Warrior. Despite his social democratic domestic politics, Healey strongly believed that furthering British interests meant containing communism in general, and Soviet influence around the globe in particular. It also meant being willing to fight, up to and including war, to protect the people of Britain and her outlying territories.

Another major factor contributing to Healey’s position was his experience as a decorated veteran of the Second World War.

After graduating from Oxford in 1940, Healey enlisted in the British army and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in April of 1941. Serving with the Royal Engineers, he saw action in the North African campaign, the Allied invasion of Sicily (1943) and the Italian campaign (1943 - 1945). He was the military landing officer (“beach master”) for the British assault brigade at Anzio in 1944. Healey later became an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire, a chivalric order) in 1945. He left the service with the rank of Major. He declined an offer to remain in the army, with the rank of Lieutenant colonel, as part of the team researching the history of the Italian campaign under Colonel David Hunt. He also decided against taking up a senior scholarship at Balliol, which might have led to an academic career. Instead, Healey joined the Labour Party, launching his political career.

Still in uniform, he gave a strongly left-wing speech to the Labour Party conference in 1945, declaring, “the upper classes in every country are selfish, depraved, dissolute and decadent”.

Needless to say, Healey made quite the impression.

Throughout the Wilson Ministry of the mid 1960s, Healey served as Secretary of State for Defence, a position which only solidified his “fighting” stance on foreign affairs. In that position, Healey helped plan and execute the early stages of the War in Rhodesia. As Shadow Defence Minister throughout the Randolph Churchill and Thatcher governments in the mid 1970s, Healey remained intimately interested in military affairs. When he became Labour leader on the eve of the ‘78 election, Healey promised not just to restore the British economy, but to protect Britain’s military strength and prestige.

Finally, there were, of course, political considerations.

While public opinion polling in the UK proper was not available to the Healey Ministry during these early days of the crisis, the PM correctly predicted that the British people would overwhelmingly favor a military response to Argentina’s aggression. Indeed, if Healey did not pursue a spirited defense of the Falklands, it was very possible that the Tories, now under their newly elected leader Geoffrey Howe, would bludgeon Labour with their inaction and ride the issue to victory in subsequent elections, presently scheduled for sometime in 1983. This was in addition to public opinion in the Islands themselves which, again, overwhelmingly favored continued union with Britain.

Though Healey respected Benn and Foot personally and professionally, he also felt that his wayward ministers were his chief rivals within the cabinet for leadership of the Labour Party. Indeed, both Benn and Foot had run against Healey in the last leadership election and finished third and second, respectively. The PM could not help but wonder to what degree the two men’s protests were calculated political decisions, to differentiate themselves in the eyes of their staunchly pacifist party base. A “principled stance” here could lead to possible victory for them in the party’s next leadership election.

Frankly, Healey was more than a little frustrated.

When all ministers except for Benn and Foot voted to go ahead with military intervention, Healey asked them to sign onto the order being given to Admiral Leach, as he wanted it to be unanimous. The two ministers refused. Healey then asked them both for their resignations; both were promptly submitted.

Two days later, on April 1st, Leach sent orders to a Royal Navy force carrying out exercises in the Mediterranean to prepare to sail south. Following the full-scale invasion on April 2nd, after an emergency meeting of the cabinet, approval was given to form a task force to retake the islands. This was backed up in an emergency sitting of the House of Commons the next day. Though Benn and Foot’s resignations caused a minor scandal for the PM, any hit the government took in the polls was almost immediately papered over by a “rally around the flag” effect, as patriotic Britons supported their leader in this time of crisis.

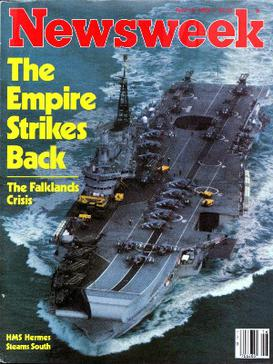

Above: Prime Minister Denis Healey, leader of the UK during the Falklands War (left); the cover of Newsweek on April 19th, 1982 (right); the title of the cover story is of course, a reference to the 1980 Star Wars sequel of the same name.

On April 6th, the British Government set up a War Cabinet to provide day-to-day political oversight of the campaign. This was the critical instrument of crisis management for the British with its sphere being to “keep under review political and military developments relating to the South Atlantic, and to report as necessary to the Defence and Overseas Policy Committee”. The War Cabinet met at least daily until it was dissolved on August 12th. Although Denis Healey is described as “dominating the War Cabinet”, Lawrence Freedman notes in the Official History of the Falklands Campaign that he “did not ignore opposition or fail to consult others. However, once a decision was reached, he ‘did not look back’”

Upon learning that the British would, in fact, use military force to retake the islands, Argentina shifted its efforts toward trying to drum up support for a UN Resolution against British intervention. Argentina’s representatives at the UN pointed to earlier resolutions calling on both sides to settle the Falklands issue through “discussion” and “arbitration”. They tried to capitalize on Benn and Foot’s resignations as “signs of discontent” with armed conflict within Westminster. Unfortunately for them, this discontent did not materialize.

Meanwhile, on April 1st, London told the UK ambassador to the UN, Peter Shore, that an invasion was imminent and that he should call an urgent meeting of the Security Council in order to get a favorable resolution against Argentina. Shore had to get 9 affirmative votes from the 15 Council members, and to avoid a blocking vote from any of the other four permanent members (The US, France, USSR, and China). The meeting took place at 11:00 am on April 3rd, New York time (4:00 pm in London). United Nations Security Council Resolution 502 was then adopted by 10 to 1 (with Panama voting against) and 4 abstentions. Significantly, the Soviet Union and China both abstained.The resolution stated that the UN Security Council was:

“Deeply disturbed at reports of an invasion on April 2nd, 1982 by armed forces of Argentina;

Determining that there exists a breach of the peace in the region of the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas),

Demands an immediate cessation of hostilities;

Demands an immediate withdrawal of all Argentine forces from the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)

Calls on the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom to seek a diplomatic solution to their differences and to respect fully the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.”

The resolution was a significant diplomatic victory for the UK; it gave the British the upper hand diplomatically by not only allowing for British military intervention (which would be a legitimate case of self-defense), but also by placing the blame for the conflict squarely on Argentina. The British also received diplomatic support from its fellow Commonwealth nations. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand all withdrew their ambassadors from Buenos Aires following the Argentine invasion.

In a surprising turn of events, not only did French president Francois Mitterrand not order his UN ambassador to veto the resolution, he also went so far as to declare an arms embargo with Argentina, “until such time as peace shall be restored in the Falklands”. France allowed UK aircraft and warships use of its port and airfield facilities at Dakar in Senegal, and provided dissimilar aircraft training so that Harrier pilots could train against the French aircraft used by Argentina.

Above: Francois Mitterrand, President of France, who surprised many by not only not opposing Britain’s use of force against Argentina, but by actively supporting their efforts. Many saw this as an attempt by Mitterrand to “pivot” back toward his fellow NATO allies.

This is not to say that the British had universal international support. Far from it. Though Chile’s government opposed Argentina’s invasion (Chile was in negotiations with Argentina for control over the Beagle Channel at the time and feared that Argentina would use similar tactics to secure the channel), as did Brazil (who officially “remained neutral”), other nations, such as Cuba and Peru, supported it. Cuba, in particular, attempted to rally either the Soviet Union or the Non-Aligned Movement to support Argentina’s actions. In response, British diplomats complained that Castro’s regime seemed to be “attempting to cynically exploit this crisis” in order to pursue normalization and recognition of its regime. Despite Cuba’s efforts, however, Asian and African nations declined to back Argentina.

The Soviets described the Falklands as a “disputed territory”, recognizing Argentina's ambitions over the islands, and called for “restraint on all sides”. While Soviet media frequently criticized both London and Washington’s actions throughout the crisis, critically, the Soviets did not veto the UK’s security council resolution at the UN. This allowed the resolution to go through without incident, signaling that Buenos Aires could not expect Soviet diplomatic support, either. Some in the Kremlin did suggest vetoing the resolution, but First Secretary Romanov declined. He argued that to do so would “needlessly antagonize the west” for no noticeable gain on the part of Moscow. Unfortunately, this sense of restraint would not win out in October, when the Soviets created a crisis of their own with Sweden.

Meanwhile, some “shuttle diplomacy” took place between the two members of NATO’s “special relationship” - the UK and the United States. On April 8th, 1982, US Secretary of State Ed Muskie arrived in London on a mission from President Robert F. Kennedy. Muskie’s objective was to provide American diplomatic support for British operations by playing the role of prospective mediator. The US’s position on the entire episode could not have been clearer. America firmly supported her British ally.

Madeleine Albright, the US Ambassador to the UN, had been among the earliest and most vocal supporters of Shore’s resolution. Indeed, although some in the United States viewed Britain’s actions as being in opposition to the Monroe Doctrine (a European power intervening in the Western Hemisphere to protect its sphere of influence), most Americans (if they were even aware of the conflict at all) supported Britain, which they viewed as the US’s chief partner on the world stage.

For his part, President Kennedy considered the matter to be an “open and shut case”. The UK was America’s chief ally. His administration considered the junta in Buenos Aires to be an illegitimate, authoritarian regime at war with its own populace. He was never going to support Argentina against Britain, especially not when the Falkland Islanders (and this was the key point to Kennedy) wanted to remain part of the UK. Kennedy ordered the CIA to provide Britain with access to relevant information gathered by American spy planes and satellites, all of which would prove invaluable during the subsequent liberation of the islands. Both chambers of the US Congress later passed resolutions supporting both the UK’s use of force and the President’s support of their actions.

The US would also provide the UK with 200 sidewinder missiles for use by their Harrier jets; along with eight Stinger surface-to-air missile systems, Harpoon anti-ship missiles and mortar bombs. On Ascension Island, the underground fuel tanks were empty when the British Task Force arrived in mid-April 1982 and the leading assault ship, HMS Fearless, did not have enough fuel to dock when it arrived off the island. The United States diverted a supertanker to replenish both the fuel tanks of ships at anchor there and the storage tanks on the island with approximately 7,600,000 liters of fuel. The Pentagon - under Secretary of Defense Scoop Jackson - further committed to providing additional support in the event that the war dragged on into the Southern Hemisphere's winter. In that scenario, the US committed tanker aircraft to support Royal Air Force missions in Europe, releasing RAF aircraft to support operations over the Falklands.

Above: Secretary of Defense Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson, who oversaw the delivery of US material aid to the British during the Falklands War.

Secretary of State Muskie attempted to arrange an emergency summit between Galtieri’s regime and the British government to avert war, but the Argentines proved elusive. Realizing that the world (even including much of Latin America) did not support their cause, they nevertheless felt confident that, having occupied the islands by force, they were “impervious” to British counter-attack.

Thus, it came to war.

The nuclear-powered submarine HMS Conqueror set sail from Scotland on April 4th. The aircraft carriers Invincible and Hermes and their escort vessels left Portsmouth, England only a day later. Hermes would serve as the flagship for the task force, around which all operations were planned. On its return to Southampton from a world cruise on April 7th, the ocean liner SS Canberra was requisitioned and set sail two days later with the Third Royal Marine Commando Brigade aboard. The ocean liner Queen Elizabeth II was also requisitioned, and left Southampton on May 12th, with the 5th Infantry Brigade on board. The whole task force eventually comprised 127 ships: 43 Royal Navy vessels, 22 Royal Fleet Auxiliary ships, and 62 merchant ships; quite the fleet, indeed.

Despite this admittedly impressive display of naval might, the retaking of the islands was, nonetheless, considered to be extremely daunting. The chances of a British counter-invasion succeeding were assessed by the US Navy as “a military impossibility”. This was largely due to the geographic isolation and remoteness of the Falkland Islands themselves. The task force’s headquarters was established by mid-April at an airbase, co-located with Wideawake Airfield, on the mid-Atlantic British overseas territory of Ascension Island. Ascension is located nearly 6,000 km away from the Falklands. Another difficulty would be Britain’s lack of deployable air cover to the region. The British had just 42 aircraft available for air combat operations: 28 Sea Harriers and 14 Harrier GR.3s. Compared to the Argentine air force, which could deploy between 50 and 120 jet fighters, the British seemed hopelessly outnumbered. The British also lacked crucial airborne early warning and control aircraft, and had to contend with the Argentine surface fleet, which boasted the powerful, French-built Exocet anti-ship missiles.

Despite the challenges they faced, the Royal Navy got to work.

After establishing their headquarters on Ascension Island, the fleet sent a small force of Royal Marines to recapture South Georgia. Meanwhile, back at headquarters, a new wing of aircraft was assembled, including Avro Vulcan B Mk 2 bombers; refueling craft; and McDonnell Douglas Phantom FGR Mk 2 fighters to protect them.

Engagements between the opposing sides began in April. The British Task Force was shadowed by Boeing 707 aircraft of the Argentine Air Force during their travel to the south. Several of these flights were intercepted by Sea Harriers outside the British-imposed Total Exclusion Zone; the unarmed 707s were not attacked because diplomatic moves were still in progress and the UK had not yet decided to commit itself to armed force. By the end of the month, however, the British established a no-fly zone over the islands to accompany their “Total Exclusion Zone”.

Above: Royal Navy FAA Sea Harrier FRS1 (left); and the Avro Vulcan B Mk 2 bomber (right); two of the primary aircraft employed by British forces in the Falklands War.

On April 21st, the first landings on South Georgia by the Special Air Service (SAS) and Special Boat Service (SBS) began. These commandos, highly trained for operations in extreme environments, were sent ahead to act as reconnaissance for the rest of the Royal Marines to follow. Despite initial setbacks, including poor weather and threats of an Argentine submarine in the vicinity, the commandos regrouped and launched a full-scale attack on the 24th. The day following, a naval and air battle broke out with the Argentine submarine Santa Fe, which was so severely damaged in the fighting that it could not submerge. The ship was later abandoned at a jetty in South Georgia. After a short forced march by the British troops and a naval bombardment demonstration by two Royal Navy vessels (Antrim and Plymouth), the Argentine forces, a total of 190 men, surrendered without resistance.

The message sent from the naval force at South Georgia to London was, “Be pleased to inform Her Majesty that the White Ensign flies alongside the Union Jack in South Georgia. God Save the Queen.” Prime Minister Healey broke the news to the media, telling them to “Toast to that news, and congratulate our forces and the Marines!” The war to retake the Falklands had begun in earnest with a British victory.

On May 1st, British operations on the Falklands proper opened with the first of five raids on the airfield at Stanley. A Vulcan bomber from Ascension Island flew a 15,000 km round trip, dropping conventional bombs across the airfield runway. The mission required repeated aerial refueling using several tanker aircraft operating in concert, including tanker-to-tanker refueling; the entire mission took its crew over 15 hours to complete.

Though the overall effect of these raids - codenamed “Operation Black Dog” - are difficult to determine, they did have a marked effect on Argentine and British morale. The Argentines realized that the British could and would strike, even from such a vast distance away. They also recognized that if the RAF could strike them at Stanley, they could also hit the Argentine mainland, if they so desired. The Argentine air force was forced to redeploy fighter aircraft from the Falklands toward the mainland further north. This served to severely undermine Argentine attempts to maintain air superiority.

Because the Falklands possessed only three airfields (one of them - at Stanley - paved), and none of these were long enough to launch fast jet aircraft, the Argentines were forced to launch their own fighters from the mainland. This delayed their reaction time and hampered their ability to respond to British attacks, to perform patrols, and to provide close air support to their soldiers on the ground. When Argentine planes did manage to reach the Exclusion Zone, jets launched from Hermes and Invincible were well-positioned to intercept them.

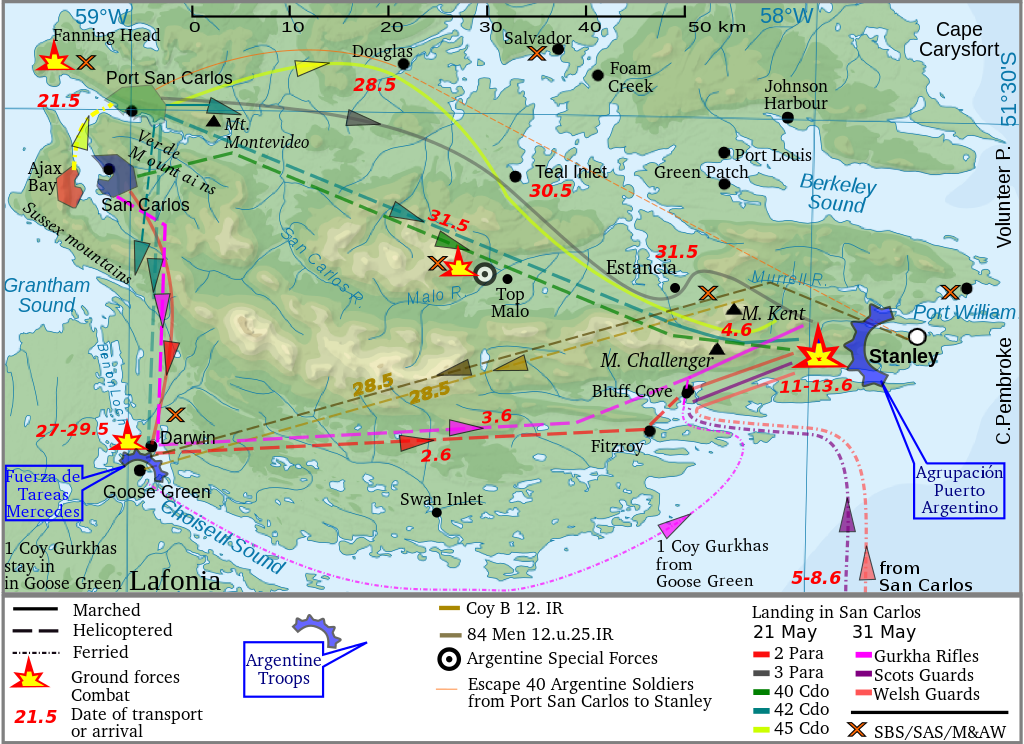

Above: A map showing Infantry deployment in the East Falklands after British landings in San Carlos.

A blow-by-blow account of the War - which wound up lasting for 2 months, 1 week, and 4 days - is not necessary.

Suffice it to say, the opening moves around South Georgia were repeated, albeit at larger scale and at greater cost in both men and material on the Falklands themselves. Throughout May, the naval and air war led to continued British victories. This was followed in June by the counter-invasion and liberation of the islands themselves, first by commandos, then by additional numbers of Royal Marines. Stanley, the capital and thrust of Argentine defenses, surrendered on June 13th. The following day, Prime Minister Healey announced a ceasefire and the commencement of negotiations for the Argentines’ surrender. A week later, on the 19th, the British retook the South Sandwich Islands as well.

In total, 901 people were killed in the 73 days of fighting - 645 from Argentina; 253 from the United Kingdom. The British also suffered 770 injured or wounded compared to 1,168 Argentines injured or wounded.

Though brief, the war was far bloodier than either side expected. For such a relatively “small” and ultimately, undeclared war, the conflict produced considerable casualties. The material loss was also far greater than expected - especially of shipping and aircraft. For a couple of “bald men fighting over a comb”, the results turned out to be pretty gruesome.

Back in the United Kingdom, Denis Healey’s popularity soared. The success of the Falklands campaign was widely regarded as a factor in the turnaround in fortunes for the Labour government, who had been slipping in opinion polls for months before the conflict began. Healey’s rival, Conservative leader Geoffrey Howe was forced to admit, “In Healey, Labour has finally found a war leader we can all rally behind.” Following the British victory in the Falklands, Labour returned to the top of the opinion polls by a wide margin and went on to win the following year's general election in a landslide. Subsequently, any planned cuts for the budget of the Royal Navy were quietly abandoned.

Above: Prime Minister Denis Healey (left); Labour Party logo, circa 1982 (right).

The full-British citizenship of the Islanders themselves was swiftly restored. Investments in their quality of life - including political devolution and economic liberalization - were swiftly enacted as a kind of recompense for what they’d been through. London also moved to provide the Islanders with a viable garrison of British troops and naval vessels to patrol nearby waters. Hermes, the aircraft carrier flagship of the fleet, remained in the Falklands until the airstrip at Stanley could be lengthened and upgraded to accommodate RAF jet fighters permanently. This new arrangement - informally called “Fortress Falklands” - showed the world a reinvigorated Britain, committed to a confident, powerful defense policy, even under Labour. Many in popular culture would call the war “a last hurrah for the British Empire”.

In Argentina, the war led to the collapse of the military junta. Having humiliated the nation on the international stage, any remaining confidence or good will that the military might enjoy amongst the Argentine people evaporated. Following the general election held in October of the following year, democracy returned to Buenos Aires. Raúl Alfonsín, leader of the resurgent Radical Civic Union’s progressive/social democratic wing, was elected President of Argentina in a landslide. Ironically, Alfonsín was the son of a Falkland Islander mother. He spent his first year in office undoing many of the authoritarian excesses of the junta and seeking justice for their crimes.

Above: Raúl Alfonsín, the “father of modern democracy in Argentina” (left); the logo for the Unión Cívica Radical (UCR), Alfonsín’s political party (right).

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: Personal Computing Takes Off!

Also, how different is the TTL British economy from the OTL? How does Healey deal with Britain's troubling manufacturing sector, with its uncreative management and workforce, as well as the trade unions?