Thanks.I am trying to remain focused on the Californie in this TL but America will be a big part of the next TL installment, so we will get some hints.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Californie- French California

- Thread starter The Tai-Pan

- Start date

Post #22- America

Post #22- American Negotiations

I'm Afraid of Americans

David Bowie

Franco-American relations had alternated between cool and tense since the initial acquisition of Alta Californie in 1836. While never actually claimed by the United States, many explorers, diplomats and politicians had simply assumed their eventual control over the entirety of the North American continent. The French colony had put a damper on such designs and more than a few Americans harbored dreams of eventual conquest for years after the French annexation. American exploring expeditions, such as Fremont’s missions maintained an undercurrent of anti-French tone, a pushing of boundaries and it was clear elements in Washington had not given up entirely on the West as its own sphere of influence. Compounding this was the real uncertainty of the old Alta Californie borders, many of which had been barely mapped or even explored by white settlers.

Yet sheer distance helped moderate such agitations, with the vast empty areas reducing possible points of conflict. With most western bound American settlers heading to coastal Oregon and Washington, there were few Americans who actually tested the porous boundaries and those that did, trappers and Indian traders, were hardly the nationalist patriots to cause problems. Uncertain borders mattered little when there seemed so little at stake..

Tensions rose again during the Texian War, and the resulting land grabs by the United States of both former Mexican and Texian territory. This desire for more land was enhanced by the overlapping and unclear claims of Mexico, Texas, the USA and France, much of it overlaid on a wild Southwest that was barely understood, not to mention the long standing native tribes that actually lived in the territories. War was only avoided when France and the USA agreed to a ‘joint occupation’ of the claimed territories, a system based on the previous precedence of such an agreement in the Oregon Country between the USA and the United Kingdom. Starting in 1846 the joint occupation of the Southwest was to last for ten years, and allow free flow of people and goods throughout the territory. By 1856 the assembled diplomats assumed (or perhaps, hoped) that either matters would be resolved or another extension could be managed.

Dramatic representation of the Texian War.

The occupation system was moribund from the start, of course. The disputed areas were far from both nations' areas of interest, sparsely populated and rarely traveled. After the 1846 agreement, things generally progressed peacefully with people going as they will, with little concern for politics. Native tribes wandered as they will, with little interest in such matters, while the few white trappers and traders felt much the same way. Geography helped sort matters as the areas in the west naturally fell more into the French orbit while areas to the east such as Sante Fe (the only sizable city in the region) turned toward the rising American power. Only the most rabid partisans in July Monarchy France or the young USA wanted to push for endless square miles of empty deserts and mountains.

This all changed with the Gold Rush in 1850, of course. Suddenly Californie was on the mind of millions of Americans, and the backcountry alive with thousands of American travelers. The trails through the Southwest were full of would-be Argonauts, bringing with them dreams of gold, land and, in a few cases, conquest. As enterprises, trading posts and entire American settlements sprung up overnight throughout the region, it became clear the old regulations were wholly inadequate. The Gold Rush also reignited old dreams among American politicians of a Republic from ‘sea to shining sea’, including what they still called California.

Another point of failure in the joint occupation was that of Native American policy. The contested region had, of course, been inhabited by a wide range of peoples for centuries. All had suffered major disruptions due to epidemics and violence but some, such as the Navajo, Apache and Comanche had managed to prosper in the confusion. Tribal leaders such as Geronimo or Hastiin Chʼil Haajiní were quite capable of capitalizing on the plentiful opportunities provided by the joint occupation and later the rush of gold seekers by both trading and raiding. The United States and France became increasingly frustrated at their lack of options to control such actions. Moving troops into the region was made impossible by mutual suspicion and bribery became increasingly prohibitive in cost, as the wealth of the region dramatically increased in the wake of so many new arrivals. The Americans in particular became chagrined that they were unable to guarantee protection for travelers in the region from roving bands of supposed savages.

Apache warriors, armed and quite willing to defend their lands.

These concerns rose to a fever pitch with the Argonaut Rebellion, which featured American miners as the leadership and core of the movement. Indeed, leaders such as Burnett had openly talked about American intervention as the only hope for the Rebellion. While these ambitions never came to fruition, the news that American settlers had been killed by French troops erupted like a volcano in Washington. The American president,Franklin Pierce, was an ardent imperialist and was openly talking about war with his Cabinet as news from the Argonaut Rebellion filtered in. Pierce was only dissuaded from war due to the ongoing Cuban filibuster crisis boiling over into the Spanish-American War.

Still, it was obvious to all that a new set of agreements needed to be made between the United States and France over the various western borders. Napoleon III was quite eager to come to an arrangement, and even conceded to hold the negotiations in Washington instead of Paris. The Pierce administration however, disorganized by the slavery debate and further distracted by war in the Caribbean, proved unable to coordinate such a meeting. It wasn’t until 1856 after Perice lost his bid for reelection and the war ended, that the new incoming President Stepehen Douglas pushed hard for a French conference to at least informally hammer out the details of the western territories.

Napoleon’s choice for negotiator was not based on diplomatic skill or experience but that quality he valued most above all others. Loyalty. Jean Gilbert Victor Fialin, duc de Persigny was one of Emperor's few political allies who had supported him in the years before his rise to power and had proved to be more dedicated to Bonapartism than any other. Grasping and ambitious, Fialin was given two principle objectives by his sovereign, somewhat in opposition to each other. To gain as much useful land as possible and to keep the peace with the Americans. The last thing Napoleon wanted was a war, even if the United States had recently embarrassed itself in Cuba. Defending Californie against a determined American assault would be impossible, both militarily and politically. An amicable agreement, if driven hard, would be the best for everyone.

The Duke of Persigny, dedicated follower of the French Emperor

Fialin arrived at Washington in February of 1857, causing quite a stir. The American capital was still a fairly minor city, and the arrival of a high-level French aristocrat was the cause for parties, balls and social events all over the city. At first the Duc de Persigny enjoyed the shower of attention, taking in the best that America’s capital had to offer, but soon the wait began to tire. Days turned to weeks, and still his increasingly testy entreaties to the State Department fell on deaf ears. Increasingly upset at what he saw as a negotiating tactic, the Frenchman reached out through informal channels for information on what the Americans hoped to accomplish. To his surprise, and disgust, the delay wasn’t the result of an American conspiracy to pressure or intimidate but instead simple dysfunction.

Behind closed doors, the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee was finding it impossible to choose a lead negotiator for the upcoming French talks. The reason was the same topic that was proving to be an intractable divider in nearly every aspect of American life. Slavery. The Democratic Party, which currently controlled the government, was bitterly divided between pro-slavery Southerners and an increasingly loud anti-slavery Northern faction. The problem was made worse because Pierce was still in office, albeit a lame-duck. Bitter at his loss to Douglas, Peirce inflamed matters by implying Douglas would give away ‘half of North America’ if it kept the peace. While Fialin stewed and Congress quarreled, events began moving in the West.

The news that Douglas was entering into talks with the French caused outrage in some radical Southern circles, who already mistrusted Douglas for being a Northern Democrat and willing to believe the worst of the incoming administration. Convinced Douglas would cave to the French and give away potential cotton lands, some Southern extremists decided to take matters into their own hands. Chief among these was Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, a Louisiana politician turned soldier of fortune. A veteran of several military adventures in the Caribbean and Mexico, notably having avoided the Cuba fiasco, Wheat was an imposing and effective fighter. Incensed that Washington ‘compromisers’ were about to give away supposed rightful Americans lands in the Southwest, the Lousianan decided to take action personally. He gathered several hundred like minded men and headed westward, hoping to hand Congress a fait accompli in the Southwest. Favorable to his cause, the state governments winked as the namely named ‘Southwest Tigers’ tramped across the Lone Star State, gathering arms and supplies along the way.

After an uneventful entry into the disputed area, the Tiger’s first stop was Sante Fe. Long a nexus of the long distance trade networks in the area, the city was one of the few urban centers in the Southwest, numbering over 4,000 people. Wheat’s troops followed the well-marked trails without incident and quickly arrived at the sleepy town in force. Without preamble they took over the local stockade and raised the Stars and Stripes over the city. There were no incidents as Santa Fe had long been virtually under American control and the few French merchants in town simply shrugged and went back to work. In fact the Tiger’s coup went so smoothly, Wheat began to worry about his whole enterprise. He had hoped his filibuster would upset the balance of power in the region, tipping it toward the Americans but clearly Sante Fe was not enough. The city was so close to America, no one reasonably expected it to be given to the French, no matter how the diplomatic talks went. What was intended to be a dramatic bold stroke turned into a damp squib. Wheat needed to go farther.

Santa Fe, commercial entrepot for the entire Southwest for centuries.

After talking with the locals and looking at a few maps (the Lousianan had never stepped foot in the territory before) Wheat was forced to realize there were few other tangible targets. Albuquerque was still too close to the American zone of influence and Tucson too southerly, far off the beaten track. So instead of setting his sights on a specific geographic point, Wheat decided to simply head westward until ‘it no longer became practicable’. Many of his men openly discussed reaching the Pacific Ocean or even seizing the fabled gold fields (not realizing these lay hundreds of miles to the north). With morale soaring, Wheat and his Tigers set off westward, heading into the heart of the Southwest, the promise of Manifest Destiny driving them on.

None of this was known in Washington, where the assembled Senators had finally arrived at the obvious solution to their condrumdum. Unable to decide on a single representative, the Committee named two co-diplomats, one from each faction. For the Southern division, the choice was John Slidell, Senator from Louisiana and former ambassador to Mexico. Suave, diplomatic and dedicated slavery, he was a natural choice by his allies. The Northern choice was Simon Cameron, Senator from Pennsylvania. Politically ambitious and well-connected, Cameron had long sought to be neutral in the slavery debate, cautiously siding with Douglas in the intercine Democratic struggles. Cameron was just moderate enough to slip into the spot, without outraging the Southern members.

So finally, in April of 1857, even as Wheat struck off into the desert, the Americans and French finally sat down to the first round of informal talks. Fialin, eager to finally be underway, was quickly dismayed at the schizophrenic American diplomats. Rarely meeting Slidell and Cameron together, the French soon learned to despise both of them. Claiming Slidell was slippery and Cameron grasping, the real issue lay that the two Americans could not agree on their objectives. Slidell was only interested in New Mexico, a region he and many others assumed would be fertile ground for slavery’s expansion. Cameron, conversely, was not interested in giving more power to the slavery wing of the party and focused instead on gains in the northern region, willing to give up swaths of the disputed Southwest for lands in Colorado or Utah. Indeed, Cameron went so far as to question the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, which had set the old border between Oregon and Californie.

Simon Cameron, tenacious if self-serving diplomat.

Far from taking advantage of the division, the Duc de Persigny was instead confused by the constantly shifting agreements, demands and requests. What might be hinted at in one meeting would be outright rejected the next. Adding to the morass was that what had started as a somewhat limited set of talks about the joint occupation of the Southwest had mushroomed into an airing of every American grievance. Immigration restrictions, custom duties, and Brunett’s Argonauts were just some of the issues discussed, quite apart from the entire Californie border. The talks promised to go nowhere and take a long time getting there.

Meanwhile, in the Southwest, the Legion was starting to move. While rumor of Wheat’s filibuster was only just starting to filter northwards to the United States, via various staging posts, sailing ships and rudimentary telegraphs, news had already reached Bazaine at Fort Yuma. The French Foreign Legion commander was both distressed and surprised at the American move. An unprovoked American invasion into the ‘joint occupation’ territory, occupying entire settlements. Another man might have shown fear or confusion but the battle hardened Frenchman instead saw a chance for personal glory. Chasing bandits or bullying native tribes might be useful to the empire but it was not the stuff careers were made of. Facing down or turning back an unlawful American column?

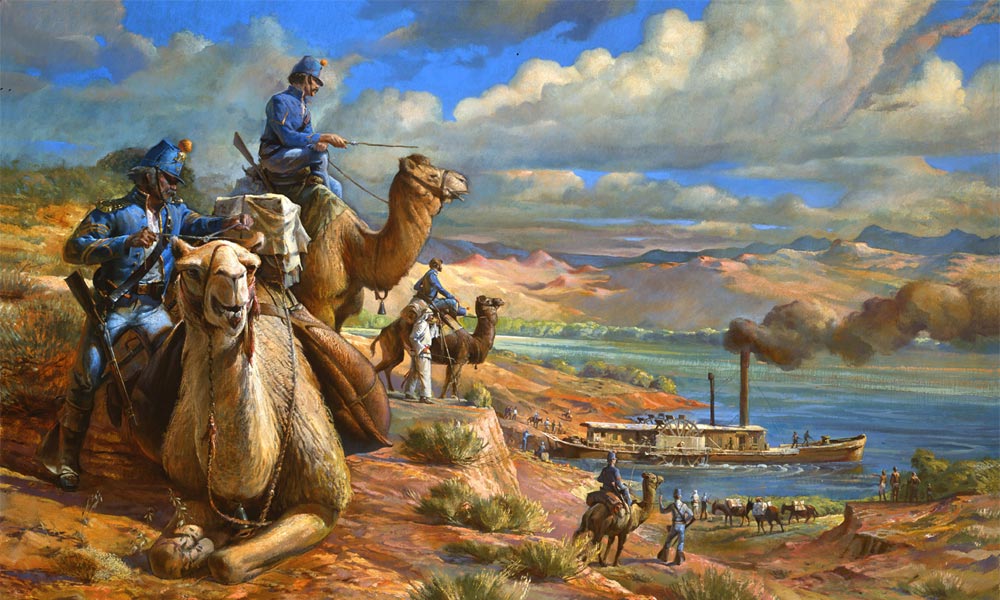

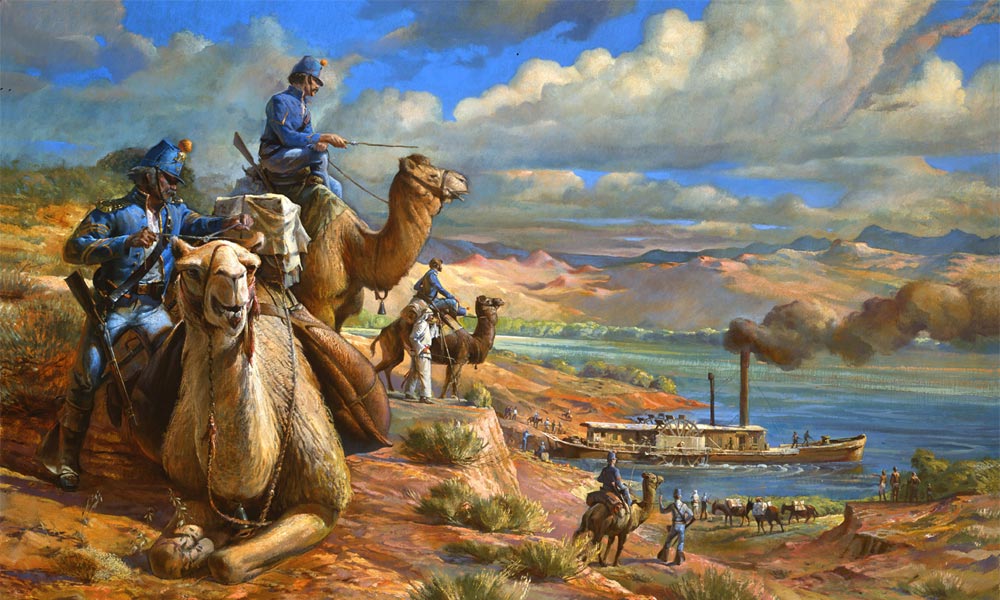

Bazaine lept into action, gathering the few hundred troops on hand and whatever supplies he could quickly scrounge. A key part of the Legion’s logistics were the Legion’s first batch of African camels, laboriously imported from Algeria. Large, ornery and aggressive, the unfriendly beasts made up for their downsides with one supreme quality, almost unfathomable endurance. Capable of carrying hundreds of pounds at a time and forgoing water for days at a time, the French considered each camel worth at least four mules.

Camels being loaded at Fort Yuma ford, the Legion's secret weapon.

Apart from the camels however, the French expedition which set off in March of 1857, was a debacle. Hastily organized and poorly supplied, Bazaine was also plagued with a lack of good guides or information. Few French agents had penetrated far into the Southwest apart from a few itinerant prospectors and traders, neither of which were trustworthy partners for the military. The local native groups on good terms with the French also rarely ventured eastward, and were of limited help outside of acting as laborers or hunters. Right from the start, the French column suffered from a lack of water and murderously difficult terrain. Matters were made worse when Bazaine blundered into conflict with the local Yavapai people, who had previously generally avoided contacts with white settlers. Bazaine had taken to draining waterholes for his thrifty men and animals however, and provoked several night time raids by the natives. Bedraggled, thirsty and tired, the Legion only survived due to their innate toughness and the ever stoic camels.

Even as Failian haggled with the Americans in Washington over borders, the two empires were on a collision course in the distant Southwest.

I'm Afraid of Americans

David Bowie

Franco-American relations had alternated between cool and tense since the initial acquisition of Alta Californie in 1836. While never actually claimed by the United States, many explorers, diplomats and politicians had simply assumed their eventual control over the entirety of the North American continent. The French colony had put a damper on such designs and more than a few Americans harbored dreams of eventual conquest for years after the French annexation. American exploring expeditions, such as Fremont’s missions maintained an undercurrent of anti-French tone, a pushing of boundaries and it was clear elements in Washington had not given up entirely on the West as its own sphere of influence. Compounding this was the real uncertainty of the old Alta Californie borders, many of which had been barely mapped or even explored by white settlers.

Yet sheer distance helped moderate such agitations, with the vast empty areas reducing possible points of conflict. With most western bound American settlers heading to coastal Oregon and Washington, there were few Americans who actually tested the porous boundaries and those that did, trappers and Indian traders, were hardly the nationalist patriots to cause problems. Uncertain borders mattered little when there seemed so little at stake..

Tensions rose again during the Texian War, and the resulting land grabs by the United States of both former Mexican and Texian territory. This desire for more land was enhanced by the overlapping and unclear claims of Mexico, Texas, the USA and France, much of it overlaid on a wild Southwest that was barely understood, not to mention the long standing native tribes that actually lived in the territories. War was only avoided when France and the USA agreed to a ‘joint occupation’ of the claimed territories, a system based on the previous precedence of such an agreement in the Oregon Country between the USA and the United Kingdom. Starting in 1846 the joint occupation of the Southwest was to last for ten years, and allow free flow of people and goods throughout the territory. By 1856 the assembled diplomats assumed (or perhaps, hoped) that either matters would be resolved or another extension could be managed.

Dramatic representation of the Texian War.

The occupation system was moribund from the start, of course. The disputed areas were far from both nations' areas of interest, sparsely populated and rarely traveled. After the 1846 agreement, things generally progressed peacefully with people going as they will, with little concern for politics. Native tribes wandered as they will, with little interest in such matters, while the few white trappers and traders felt much the same way. Geography helped sort matters as the areas in the west naturally fell more into the French orbit while areas to the east such as Sante Fe (the only sizable city in the region) turned toward the rising American power. Only the most rabid partisans in July Monarchy France or the young USA wanted to push for endless square miles of empty deserts and mountains.

This all changed with the Gold Rush in 1850, of course. Suddenly Californie was on the mind of millions of Americans, and the backcountry alive with thousands of American travelers. The trails through the Southwest were full of would-be Argonauts, bringing with them dreams of gold, land and, in a few cases, conquest. As enterprises, trading posts and entire American settlements sprung up overnight throughout the region, it became clear the old regulations were wholly inadequate. The Gold Rush also reignited old dreams among American politicians of a Republic from ‘sea to shining sea’, including what they still called California.

Another point of failure in the joint occupation was that of Native American policy. The contested region had, of course, been inhabited by a wide range of peoples for centuries. All had suffered major disruptions due to epidemics and violence but some, such as the Navajo, Apache and Comanche had managed to prosper in the confusion. Tribal leaders such as Geronimo or Hastiin Chʼil Haajiní were quite capable of capitalizing on the plentiful opportunities provided by the joint occupation and later the rush of gold seekers by both trading and raiding. The United States and France became increasingly frustrated at their lack of options to control such actions. Moving troops into the region was made impossible by mutual suspicion and bribery became increasingly prohibitive in cost, as the wealth of the region dramatically increased in the wake of so many new arrivals. The Americans in particular became chagrined that they were unable to guarantee protection for travelers in the region from roving bands of supposed savages.

Apache warriors, armed and quite willing to defend their lands.

These concerns rose to a fever pitch with the Argonaut Rebellion, which featured American miners as the leadership and core of the movement. Indeed, leaders such as Burnett had openly talked about American intervention as the only hope for the Rebellion. While these ambitions never came to fruition, the news that American settlers had been killed by French troops erupted like a volcano in Washington. The American president,Franklin Pierce, was an ardent imperialist and was openly talking about war with his Cabinet as news from the Argonaut Rebellion filtered in. Pierce was only dissuaded from war due to the ongoing Cuban filibuster crisis boiling over into the Spanish-American War.

Still, it was obvious to all that a new set of agreements needed to be made between the United States and France over the various western borders. Napoleon III was quite eager to come to an arrangement, and even conceded to hold the negotiations in Washington instead of Paris. The Pierce administration however, disorganized by the slavery debate and further distracted by war in the Caribbean, proved unable to coordinate such a meeting. It wasn’t until 1856 after Perice lost his bid for reelection and the war ended, that the new incoming President Stepehen Douglas pushed hard for a French conference to at least informally hammer out the details of the western territories.

Napoleon’s choice for negotiator was not based on diplomatic skill or experience but that quality he valued most above all others. Loyalty. Jean Gilbert Victor Fialin, duc de Persigny was one of Emperor's few political allies who had supported him in the years before his rise to power and had proved to be more dedicated to Bonapartism than any other. Grasping and ambitious, Fialin was given two principle objectives by his sovereign, somewhat in opposition to each other. To gain as much useful land as possible and to keep the peace with the Americans. The last thing Napoleon wanted was a war, even if the United States had recently embarrassed itself in Cuba. Defending Californie against a determined American assault would be impossible, both militarily and politically. An amicable agreement, if driven hard, would be the best for everyone.

The Duke of Persigny, dedicated follower of the French Emperor

Fialin arrived at Washington in February of 1857, causing quite a stir. The American capital was still a fairly minor city, and the arrival of a high-level French aristocrat was the cause for parties, balls and social events all over the city. At first the Duc de Persigny enjoyed the shower of attention, taking in the best that America’s capital had to offer, but soon the wait began to tire. Days turned to weeks, and still his increasingly testy entreaties to the State Department fell on deaf ears. Increasingly upset at what he saw as a negotiating tactic, the Frenchman reached out through informal channels for information on what the Americans hoped to accomplish. To his surprise, and disgust, the delay wasn’t the result of an American conspiracy to pressure or intimidate but instead simple dysfunction.

Behind closed doors, the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee was finding it impossible to choose a lead negotiator for the upcoming French talks. The reason was the same topic that was proving to be an intractable divider in nearly every aspect of American life. Slavery. The Democratic Party, which currently controlled the government, was bitterly divided between pro-slavery Southerners and an increasingly loud anti-slavery Northern faction. The problem was made worse because Pierce was still in office, albeit a lame-duck. Bitter at his loss to Douglas, Peirce inflamed matters by implying Douglas would give away ‘half of North America’ if it kept the peace. While Fialin stewed and Congress quarreled, events began moving in the West.

The news that Douglas was entering into talks with the French caused outrage in some radical Southern circles, who already mistrusted Douglas for being a Northern Democrat and willing to believe the worst of the incoming administration. Convinced Douglas would cave to the French and give away potential cotton lands, some Southern extremists decided to take matters into their own hands. Chief among these was Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, a Louisiana politician turned soldier of fortune. A veteran of several military adventures in the Caribbean and Mexico, notably having avoided the Cuba fiasco, Wheat was an imposing and effective fighter. Incensed that Washington ‘compromisers’ were about to give away supposed rightful Americans lands in the Southwest, the Lousianan decided to take action personally. He gathered several hundred like minded men and headed westward, hoping to hand Congress a fait accompli in the Southwest. Favorable to his cause, the state governments winked as the namely named ‘Southwest Tigers’ tramped across the Lone Star State, gathering arms and supplies along the way.

After an uneventful entry into the disputed area, the Tiger’s first stop was Sante Fe. Long a nexus of the long distance trade networks in the area, the city was one of the few urban centers in the Southwest, numbering over 4,000 people. Wheat’s troops followed the well-marked trails without incident and quickly arrived at the sleepy town in force. Without preamble they took over the local stockade and raised the Stars and Stripes over the city. There were no incidents as Santa Fe had long been virtually under American control and the few French merchants in town simply shrugged and went back to work. In fact the Tiger’s coup went so smoothly, Wheat began to worry about his whole enterprise. He had hoped his filibuster would upset the balance of power in the region, tipping it toward the Americans but clearly Sante Fe was not enough. The city was so close to America, no one reasonably expected it to be given to the French, no matter how the diplomatic talks went. What was intended to be a dramatic bold stroke turned into a damp squib. Wheat needed to go farther.

Santa Fe, commercial entrepot for the entire Southwest for centuries.

After talking with the locals and looking at a few maps (the Lousianan had never stepped foot in the territory before) Wheat was forced to realize there were few other tangible targets. Albuquerque was still too close to the American zone of influence and Tucson too southerly, far off the beaten track. So instead of setting his sights on a specific geographic point, Wheat decided to simply head westward until ‘it no longer became practicable’. Many of his men openly discussed reaching the Pacific Ocean or even seizing the fabled gold fields (not realizing these lay hundreds of miles to the north). With morale soaring, Wheat and his Tigers set off westward, heading into the heart of the Southwest, the promise of Manifest Destiny driving them on.

None of this was known in Washington, where the assembled Senators had finally arrived at the obvious solution to their condrumdum. Unable to decide on a single representative, the Committee named two co-diplomats, one from each faction. For the Southern division, the choice was John Slidell, Senator from Louisiana and former ambassador to Mexico. Suave, diplomatic and dedicated slavery, he was a natural choice by his allies. The Northern choice was Simon Cameron, Senator from Pennsylvania. Politically ambitious and well-connected, Cameron had long sought to be neutral in the slavery debate, cautiously siding with Douglas in the intercine Democratic struggles. Cameron was just moderate enough to slip into the spot, without outraging the Southern members.

So finally, in April of 1857, even as Wheat struck off into the desert, the Americans and French finally sat down to the first round of informal talks. Fialin, eager to finally be underway, was quickly dismayed at the schizophrenic American diplomats. Rarely meeting Slidell and Cameron together, the French soon learned to despise both of them. Claiming Slidell was slippery and Cameron grasping, the real issue lay that the two Americans could not agree on their objectives. Slidell was only interested in New Mexico, a region he and many others assumed would be fertile ground for slavery’s expansion. Cameron, conversely, was not interested in giving more power to the slavery wing of the party and focused instead on gains in the northern region, willing to give up swaths of the disputed Southwest for lands in Colorado or Utah. Indeed, Cameron went so far as to question the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, which had set the old border between Oregon and Californie.

Simon Cameron, tenacious if self-serving diplomat.

Far from taking advantage of the division, the Duc de Persigny was instead confused by the constantly shifting agreements, demands and requests. What might be hinted at in one meeting would be outright rejected the next. Adding to the morass was that what had started as a somewhat limited set of talks about the joint occupation of the Southwest had mushroomed into an airing of every American grievance. Immigration restrictions, custom duties, and Brunett’s Argonauts were just some of the issues discussed, quite apart from the entire Californie border. The talks promised to go nowhere and take a long time getting there.

Meanwhile, in the Southwest, the Legion was starting to move. While rumor of Wheat’s filibuster was only just starting to filter northwards to the United States, via various staging posts, sailing ships and rudimentary telegraphs, news had already reached Bazaine at Fort Yuma. The French Foreign Legion commander was both distressed and surprised at the American move. An unprovoked American invasion into the ‘joint occupation’ territory, occupying entire settlements. Another man might have shown fear or confusion but the battle hardened Frenchman instead saw a chance for personal glory. Chasing bandits or bullying native tribes might be useful to the empire but it was not the stuff careers were made of. Facing down or turning back an unlawful American column?

Bazaine lept into action, gathering the few hundred troops on hand and whatever supplies he could quickly scrounge. A key part of the Legion’s logistics were the Legion’s first batch of African camels, laboriously imported from Algeria. Large, ornery and aggressive, the unfriendly beasts made up for their downsides with one supreme quality, almost unfathomable endurance. Capable of carrying hundreds of pounds at a time and forgoing water for days at a time, the French considered each camel worth at least four mules.

Camels being loaded at Fort Yuma ford, the Legion's secret weapon.

Apart from the camels however, the French expedition which set off in March of 1857, was a debacle. Hastily organized and poorly supplied, Bazaine was also plagued with a lack of good guides or information. Few French agents had penetrated far into the Southwest apart from a few itinerant prospectors and traders, neither of which were trustworthy partners for the military. The local native groups on good terms with the French also rarely ventured eastward, and were of limited help outside of acting as laborers or hunters. Right from the start, the French column suffered from a lack of water and murderously difficult terrain. Matters were made worse when Bazaine blundered into conflict with the local Yavapai people, who had previously generally avoided contacts with white settlers. Bazaine had taken to draining waterholes for his thrifty men and animals however, and provoked several night time raids by the natives. Bedraggled, thirsty and tired, the Legion only survived due to their innate toughness and the ever stoic camels.

Even as Failian haggled with the Americans in Washington over borders, the two empires were on a collision course in the distant Southwest.

The Duc was chosen for loyalty, but does he not have a staff who would realize what's happening?Far from taking advantage of the division, the Duc de Persigny was instead confused by the constantly shifting agreements, demands and requests.

Yes (although 'staff' in this period would be crazy tiny by our modern standards), but it is still hard to come to an agreement with a bunch of oscillating Americans. It isn't the Duke's fault, more just a difficult circumstance. The Americans were just not quite feeling the urgency at that stage.The Duc was chosen for loyalty, but does he not have a staff who would realize what's happening?

Wheat will fix that.

Oof, things were already looking bleak in terms of diplomacy because of the sloppy organisation on the part of the Americans; but with a half-baked filibuster underway it will probably get far worse before it gets better.

I could imagine 3 different ways this would go down and only the third one offers any semblance of hope.

1. If negotiations go in favour of the French, it would not only cause anger in American political circles but also might be part of an early catalyst for the Civil war with TTL's Confederate seeing the federal government as too weak and pussyfoot to resist demands made by the French government and protect American interests (with Wheat becoming either a poster boy or a Martyr for Manifest destiny and American pride) It could also mean more settlers will head towards to Spanish colony's that America are sure to gain; becoming a more attractive option after Alta California is blocked to them.

2. If negotiations go in favour of the Americans I imagine that France will be thrown into an unstable situation with those at home seeing the government unable to protect rightful French land from rebellion and filibusters. It'll be seen by the people of France as another sign of incompetence from Napoleon III and a potential catalyst for the downfall of the July Monarchy. (Unless some of his other foreign policy and domestic blunders have been butterflied away which will still leave ol' Napoleon 3 in a precarious position)

3. The best option (which is still a ticking timebomb) is to reorganize the territory into a sort of independent state for the Native Americans who are currently living there. This means the French and Americans technically don't gain or lose anymore land but they would still influence the new state in a myriad of different ways. (But this all would have to hinge on the Native Tribes being seen as people which a lot of Americans and French alike wouldn't in this time period. That's not even mentioning the vast amount of tribes and how they all see themselves, their relationship with each other and their attitudes from this hypothetical new country.)

Whatever way you cut it, things are about to get messy and the fates of millions will potentially be decided in a battle between a fervent slaver / mercenary & a glory hound general.

Anyway great update as always and I'm excited to see where things go from here.

I could imagine 3 different ways this would go down and only the third one offers any semblance of hope.

1. If negotiations go in favour of the French, it would not only cause anger in American political circles but also might be part of an early catalyst for the Civil war with TTL's Confederate seeing the federal government as too weak and pussyfoot to resist demands made by the French government and protect American interests (with Wheat becoming either a poster boy or a Martyr for Manifest destiny and American pride) It could also mean more settlers will head towards to Spanish colony's that America are sure to gain; becoming a more attractive option after Alta California is blocked to them.

2. If negotiations go in favour of the Americans I imagine that France will be thrown into an unstable situation with those at home seeing the government unable to protect rightful French land from rebellion and filibusters. It'll be seen by the people of France as another sign of incompetence from Napoleon III and a potential catalyst for the downfall of the July Monarchy. (Unless some of his other foreign policy and domestic blunders have been butterflied away which will still leave ol' Napoleon 3 in a precarious position)

3. The best option (which is still a ticking timebomb) is to reorganize the territory into a sort of independent state for the Native Americans who are currently living there. This means the French and Americans technically don't gain or lose anymore land but they would still influence the new state in a myriad of different ways. (But this all would have to hinge on the Native Tribes being seen as people which a lot of Americans and French alike wouldn't in this time period. That's not even mentioning the vast amount of tribes and how they all see themselves, their relationship with each other and their attitudes from this hypothetical new country.)

Whatever way you cut it, things are about to get messy and the fates of millions will potentially be decided in a battle between a fervent slaver / mercenary & a glory hound general.

Anyway great update as always and I'm excited to see where things go from here.

I predict Wheat and his “Southwest Tigers” will lose to the French Foreign Legion and the incident will greatly inflame the French delegation and they (the French) will demand a cessation of American ambitions in the west and for Washington to rein in “independently-minded elements” at the very least.

With the American delegation incapable of showing a united front against France, they (the Americans) cave to French demands.

With the American delegation incapable of showing a united front against France, they (the Americans) cave to French demands.

The July Monarchy was in place during thr old 1846 round of talks, when mentioned. It had been overthrown, like OTL.I may have read it wrong, but if Napoleon is in power, then wasn't the Second Empire proclaimed, so how is the July Monarchy still in place?

Anyway, this is an excellent chapter, and I can't wait to see how the Franco-American confrontation unfolds and the impact on negotiations.

The upcoming debacle between the Foreign Legion and the Filibusters gave me a good laugh, and reminded me of the 1859 Pig War for some reasonPost #22- American Negotiations

SNIP

Pig War crossed with Fashoda. Thank you for the kind words.The upcoming debacle between the Foreign Legion and the Filibusters gave me a good laugh, and reminded me of the 1859 Pig War for some reason

I can't say I've heard of Fashoda beforePig War crossed with Fashoda. Thank you for the kind words.

One of the golden oldies of the AH world.I can't say I've heard of Fashoda before

Fashoda Incident - Wikipedia

That makes it funnier, it gives a sense of irony that in which the French sorta got an upper hand in this timeline.

twovultures

Donor

A little bit of OTL Arizona is cotton-suitable, but I think the push west by slavocrat raiders is based more on wishful thinking than a sober analysis of the land's potential.Are the disputed territories even suitable for cotton or other labor intensive crops? They might only be useful for expanding the south's representation in Congress.

A little bit of OTL Arizona is cotton-suitable, but I think the push west by slavocrat raiders is based more on wishful thinking than a sober analysis of the land's potential.

Exactly, the Southwestern US is not suitable for the intentions of Southern Slavers at all. Their ideas seem more in line with a HOI4 player who wants to map paint and create big borders that anything materially concrete.

That's why I think we might see butterflies in the Carribbean with Southern politicians and landholders wanting to secure land to grow Cotton & other cash crops in a more suitable climate but also as a way to lick their wounds and hurt pride (e.g. "If we can't have Arizona for cotton and a new state, why not have Cuba serve the same purpose?)

Not really. Cotton was (and IS) a big product of Arizona but that came much later after slavery. Slavery did exist in OTL in those areas, but it was generally Native American slaves. That said, OTL and in this TL slave oriented leaders thought the Southwest would be prime slave territory.Are the disputed territories even suitable for cotton or other labor intensive crops? They might only be useful for expanding the south's representation in Congress.

Generally yes.A little bit of OTL Arizona is cotton-suitable, but I think the push west by slavocrat raiders is based more on wishful thinking than a sober analysis of the land's potential.

For the bolded, you'll note this has already flared up. The USA just fought a war with Spain over Cuba, which ended in a stalemate and empty peace between the two powers.Exactly, the Southwestern US is not suitable for the intentions of Southern Slavers at all. Their ideas seem more in line with a HOI4 player who wants to map paint and create big borders that anything materially concrete.

That's why I think we might see butterflies in the Carribbean with Southern politicians and landholders wanting to secure land to grow Cotton & other cash crops in a more suitable climate but also as a way to lick their wounds and hurt pride (e.g. "If we can't have Arizona for cotton and a new state, why not have Cuba serve the same purpose?)

Because it depended on post-Civil War technologies and/or infrastructure?but that came much later after slavery

Been a while since I read this thread, was it a fillibuster invasion or an actual war between the Spanish and US Armed Forces?For the bolded, you'll note this has already flared up. The USA just fought a war with Spain over Cuba, which ended in a stalemate and empty peace between the two powers.

Generally large scale irrigation.Because it depended on post-Civil War technologies and/or infrastructure?

I am trying to do not get bogged down in USA history, but I imagine a failed filibuster, which lead to real USA-Spanish naval clashes and then petered out when the USA was unable/willing to land troops, and then European political pressure.Been a while since I read this thread, was it a fillibuster invasion or an actual war between the Spanish and US Armed Forces?

New slave states also means more pro-slavery votes and pro-slavery Congressmen.Exactly, the Southwestern US is not suitable for the intentions of Southern Slavers at all. Their ideas seem more in line with a HOI4 player who wants to map paint and create big borders that anything materially concrete.

Share: